diff --git a/WORKFLOW b/WORKFLOW

index 1e6900c8d5e87da0911fa9748ead24a72ab4fb16..d3e015568b60efdef70bce50b099e0ecf98326e9 100644

--- a/WORKFLOW

+++ b/WORKFLOW

@@ -24,44 +24,8 @@ Ver el archivo *gitflow*.

## Propuesta de texto

-* Moverse a la rama *queue* y agregarlo dentro del directorio *\_queue* en

- texto plano.

-

-Comandos:

-

- git checkout queue

- git add _queue/nombre-del-articulo.markdown

- git commit

-

-

-## Traducción

-

-* Desde la rama *queue*, crear una nueva rama con el articulo a traducir.

-

-* En general la traducción se hace sobre el mismo texto original, con la

- traducción de cada párrafo inmediatamente debajo del original (es decir,

- intercalados).

-

-* Para facilitar la revisión, generar un commit después por cada párrafo

- traducido.

-

-Comandos:

-

- git flow feature start nombre-del-articulo

- # Después de traducir un párrafo

- git commit -a -m "Nombre del artículo, párrafo #"

-

-

-## Revisión

-

-* Se hace una lectura de prueba y se eliminan los párrafos en el idioma

- original.

-

-* Se mergea en la rama *queue*.

-

-Comandos:

-

- git flow feature finish nombre-del-articulo

+* Podés hacernos un issue en el

+ [repositorio](https://github.com/edsl/articulos) de los artículos.

## Publicación

diff --git a/_queue/accelerate.markdown b/_queue/accelerate.markdown

deleted file mode 100644

index 491678ac7e1c27f5f1fbaaa4b1d08529850a1dec..0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

--- a/_queue/accelerate.markdown

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,296 +0,0 @@

-#ACCELERATE

-MANIFESTO FOR AN ACCELERATIONIST POLITICS

-01. INTRODUCTION: On the Conjuncture

-1. At the beginning of the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, global civilization faces

-a new breed of cataclysm. These coming apocalypses ridicule the norms and organisational

-structures of the politics which were forged in the birth of the nation-state, the rise of

-capitalism, and a Twentieth Century of unprecedented wars.

-2. Most significant is the breakdown of the planetary climatic system. In time, this threatens

-the continued existence of the present global human population. Though this is the most

-critical of the threats which face humanity, a series of lesser but potentially equally

-destabilising problems exist alongside and intersect with it. Terminal resource depletion,

-especially in water and energy reserves, offers the prospect of mass starvation, collapsing

-economic paradigms, and new hot and cold wars. Continued financial crisis has led

-governments to embrace the paralyzing death spiral policies of austerity, privatisation of

-social welfare services, mass unemployment, and stagnating wages. Increasing automation in

-production processes – including ‘intellectual labour’ – is evidence of the secular crisis of

-capitalism, soon to render it incapable of maintaining current standards of living for even the

-former middle classes of the global north.

-3. In contrast to these ever-accelerating catastrophes, today’s politics is beset by an inability

-to generate the new ideas and modes of organisation necessary to transform our societies to

-confront and resolve the coming annihilations. While crisis gathers force and speed, politics

-withers and retreats. In this paralysis of the political imaginary, the future has been cancelled.

-4. Since 1979, the hegemonic global political ideology has been neoliberalism, found in some

-variant throughout the leading economic powers. In spite of the deep structural challenges the

-new global problems present to it, most immediately the credit, financial, and fiscal crises

-since 2007-8, neoliberal programmes have only evolved in the sense of deepening. This

-continuation of the neoliberal project, or neoliberalism 2.0, has begun to apply another round

-of structural adjustments, most significantly in the form of encouraging new and aggressive

-incursions by the private sector into what remains of social democratic institutions and

-services. This is in spite of the immediately negative economic and social effects of such

-policies, and the longer term fundamental barriers posed by the new global crises.

-5. That the forces of right wing governmental, non-governmental, and corporate power have

-been able to press forth with neoliberalisation is at least in part a result of the continued

-paralysis and ineffectual nature of much what remains of the left. Thirty years of neoliberalism

-have rendered most left-leaning political parties bereft of radical thought, hollowed out, and

-without a popular mandate. At best they have responded to our present crises with calls for a

-return to a Keynesian economics, in spite of the evidence that the very conditions which

-enabled post-war social democracy to occur no longer exist. We cannot return to mass

-industrial-Fordist labour by fiat, if at all. Even the neosocialist regimes of South America’s

-Bolivarian Revolution, whilst heartening in their ability to resist the dogmas of contemporary

-capitalism, remain disappointingly unable to advance an alternative beyond mid-Twentieth

-Century socialism. Organised labour, being systematically weakened by the changes wrought

-in the neoliberal project, is sclerotic at an institutional level and – at best – capable only of

-mildly mitigating the new structural adjustments. But with no systematic approach to building

-a new economy, or the structural solidarity to push such changes through, for now labour

-remains relatively impotent. The new social movements which emerged since the end of the

-Cold War, experiencing a resurgence in the years after 2008, have been similarly unable to

-devise a new political ideological vision. Instead they expend considerable energy on internal

-direct-democratic process and affective self-valorisation over strategic efficacy, and frequently

-propound a variant of neo-primitivist localism, as if to if to oppose the abstract violence of

-globalised capital with the flimsy and ephemeral “authenticity” of communal immediacy.

-

-6. In the absence of a radically new social, political, organisational, and economic vision the

-hegemonic powers of the right will continue to be able to push forward their narrow-minded

-imaginary, in the face of any and all evidence. At best, the left may be able for a time to

-partially resist some of the worst incursions. But this is to be Canute against an ultimately

-irresistible tide. To generate a new left global hegemony entails a recovery of lost possible

-futures, and indeed the recovery of the future as such.

-

-02. INTEREGNUM: On Accelerationisms

-1. If any system has been associated with ideas of acceleration it is capitalism. The essential

-metabolism of capitalism demands economic growth, with competition between individual

-capitalist entities setting in motion increasing technological developments in an attempt to

-achieve competitive advantage, all accompanied by increasing social dislocation. In its

-neoliberal form, its ideological self-presentation is one of liberating the forces of creative

-destruction, setting free ever-accelerating technological and social innovations.

-2. The philosopher Nick Land captured this most acutely, with a myopic yet hypnotising belief

-that capitalist speed alone could generate a global transition towards unparalleled

-technological singularity. In this visioning of capital, the human can eventually be discarded as

-mere drag to an abstract planetary intelligence rapidly constructing itself from the bricolaged

-fragments of former civilisations. However Landian neoliberalism confuses speed with

-acceleration. We may be moving fast, but only within a strictly defined set of capitalist

-parameters that themselves never waver. We experience only the increasing speed of a local

-horizon, a simple brain-dead onrush rather than an acceleration which is also navigational, an

-experimental process of discovery within a universal space of possibility. It is the latter mode

-of acceleration which we hold as essential.

-3. Even worse, as Deleuze and Guattari recognized, from the very beginning what capitalist

-speed deterritorializes with one hand, it reterritorializes with the other. Progress becomes

-constrained within a framework of surplus value, a reserve army of labour, and free-floating

-capital. Modernity is reduced to statistical measures of economic growth and social innovation

-becomes encrusted with kitsch remainders from our communal past. Thatcherite-Reaganite

-deregulation sits comfortably alongside Victorian ‘back-to-basics’ family and religious values.

-4. A deeper tension within neoliberalism is in terms of its self-image as the vehicle of

-modernity, as literally synonymous with modernisation, whilst promising a future that it is

-constitutively incapable of providing. Indeed, as neoliberalism has progressed, rather than

-enabling individual creativity, it has tended towards eliminating cognitive inventiveness in

-favour of an affective production line of scripted interactions, coupled to global supply chains

-and a neo-Fordist Eastern production zone. A vanishingly small cognitariat of elite intellectual

-workers shrinks with each passing year – and increasingly so as algorithmic automation

-winds its way through the spheres of affective and intellectual labour. Neoliberalism, though

-positing itself as a necessary historical development, was in fact a merely contingent means

-to ward off the crisis of value that emerged in the 1970s. Inevitably this was a sublimation of

-the crisis rather than its ultimate overcoming.

-5. It is Marx, along with Land, who remains the paradigmatic accelerationist thinker. Contrary

-to the all-too familiar critique, and even the behaviour of some contemporary Marxians, we

-must remember that Marx himself used the most advanced theoretical tools and empirical

-data available in an attempt to fully understand and transform his world. He was not a thinker

-who resisted modernity, but rather one who sought to analyse and intervene within it,

-understanding that for all its exploitation and corruption, capitalism remained the most

-advanced economic system to date. Its gains were not to be reversed, but accelerated

-beyond the constraints the capitalist value form.

-6. Indeed, as even Lenin wrote in the 1918 text “Left Wing” Childishness:

-"Socialism is inconceivable without large-scale capitalist engineering based on the

-latest discoveries of modern science. It is inconceivable without planned state

-

-organisation which keeps tens of millions of people to the strictest observance of a

-unified standard in production and distribution. We Marxists have always spoken of

-this, and it is not worth while wasting two seconds talking to people who do not

-understand even this (anarchists and a good half of the Left SocialistRevolutionaries)."

-7. As Marx was aware, capitalism cannot be identified as the agent of true acceleration.

-Similarly, the assessment of left politics as antithetical to technosocial acceleration is also, at

-least in part, a severe misrepresentation. Indeed, if the political left is to have a future it must

-be one in which it maximally embraces this suppressed accelerationist tendency.

-

-03: MANIFEST: On the Future

-1. We believe the most important division in today’s left is between those that hold to a folk

-politics of localism, direct action, and relentless horizontalism, and those that outline what

-must become called an accelerationist politics at ease with a modernity of abstraction,

-complexity, globality, and technology. The former remains content with establishing small and

-temporary spaces of non-capitalist social relations, eschewing the real problems entailed in

-facing foes which are intrinsically non-local, abstract, and rooted deep in our everyday

-infrastructure. The failure of such politics has been built-in from the very beginning. By

-contrast, an accelerationist politics seeks to preserve the gains of late capitalism while going

-further than its value system, governance structures, and mass pathologies will allow.

-2. All of us want to work less. It is an intriguing question as to why it was that the world’s

-leading economist of the post-war era believed that an enlightened capitalism inevitably

-progressed towards a radical reduction of working hours. In The Economic Prospects for Our

-Grandchildren (written in 1930), Keynes forecast a capitalist future where individuals would

-have their work reduced to three hours a day. What has instead occurred is the progressive

-elimination of the work-life distinction, with work coming to permeate every aspect of the

-emerging social factory.

-3. Capitalism has begun to constrain the productive forces of technology, or at least, direct

-them towards needlessly narrow ends. Patent wars and idea monopolisation are

-contemporary phenomena that point to both capital’s need to move beyond competition, and

-capital’s increasingly retrograde approach to technology. The properly accelerative gains of

-neoliberalism have not led to less work or less stress. And rather than a world of space travel,

-future shock, and revolutionary technological potential, we exist in a time where the only thing

-which develops is marginally better consumer gadgetry. Relentless iterations of the same

-basic product sustain marginal consumer demand at the expense of human acceleration.

-4. We do not want to return to Fordism. There can be no return to Fordism. The capitalist

-“golden era” was premised on the production paradigm of the orderly factory environment,

-where (male) workers received security and a basic standard of living in return for a lifetime of

-stultifying boredom and social repression. Such a system relied upon an international

-hierarchy of colonies, empires, and an underdeveloped periphery; a national hierarchy of

-racism and sexism; and a rigid family hierarchy of female subjugation. For all the nostalgia

-many may feel, this regime is both undesirable and practically impossible to return to.

-5. Accelerationists want to unleash latent productive forces. In this project, the material

-platform of neoliberalism does not need to be destroyed. It needs to be repurposed towards

-common ends. The existing infrastructure is not a capitalist stage to be smashed, but a

-springboard to launch towards post-capitalism.

-6. Given the enslavement of technoscience to capitalist objectives (especially since the late

-1970s) we surely do not yet know what a modern technosocial body can do. Who amongst us

-fully recognizes what untapped potentials await in the technology which has already been

-developed? Our wager is that the true transformative potentials of much of our technological

-and scientific research remain unexploited, filled with presently redundant features (or pre-

-

-adaptations) that, following a shift beyond the short-sighted capitalist socius, can become

-decisive.

-7. We want to accelerate the process of technological evolution. But what we are arguing for

-is not techno-utopianism. Never believe that technology will be sufficient to save us.

-Necessary, yes, but never sufficient without socio-political action. Technology and the social

-are intimately bound up with one another, and changes in either potentiate and reinforce

-changes in the other. Whereas the techno-utopians argue for acceleration on the basis that it

-will automatically overcome social conflict, our position is that technology should be

-accelerated precisely because it is needed in order to win social conflicts.

-8. We believe that any post-capitalism will require post-capitalist planning. The faith placed in

-the idea that, after a revolution, the people will spontaneously constitute a novel

-socioeconomic system that isn’t simply a return to capitalism is naïve at best, and ignorant at

-worst. To further this, we must develop both a cognitive map of the existing system and a

-speculative image of the future economic system.

-9. To do so, the left must take advantage of every technological and scientific advance made

-possible by capitalist society. We declare that quantification is not an evil to be eliminated, but

-a tool to be used in the most effective manner possible. Economic modelling is – simply put –

-a necessity for making intelligible a complex world. The 2008 financial crisis reveals the risks

-of blindly accepting mathematical models on faith, yet this is a problem of illegitimate authority

-not of mathematics itself. The tools to be found in social network analysis, agent-based

-modelling, big data analytics, and non-equilibrium economic models, are necessary cognitive

-mediators for understanding complex systems like the modern economy. The accelerationist

-left must become literate in these technical fields.

-10. Any transformation of society must involve economic and social experimentation. The

-Chilean Project Cybersyn is emblematic of this experimental attitude – fusing advanced

-cybernetic technologies, with sophisticated economic modelling, and a democratic platform

-instantiated in the technological infrastructure itself. Similar experiments were conducted in

-1950s-1960s Soviet economics as well, employing cybernetics and linear programming in an

-attempt to overcome the new problems faced by the first communist economy. That both of

-these were ultimately unsuccessful can be traced to the political and technological constraints

-these early cyberneticians operated under.

-11. The left must develop sociotechnical hegemony: both in the sphere of ideas, and in the

-sphere of material platforms. Platforms are the infrastructure of global society. They establish

-the basic parameters of what is possible, both behaviourally and ideologically. In this sense,

-they embody the material transcendental of society: they are what make possible particular

-sets of actions, relationships, and powers. While much of the current global platform is biased

-towards capitalist social relations, this is not an inevitable necessity. These material platforms

-of production, finance, logistics, and consumption can and will be reprogrammed and

-reformatted towards post-capitalist ends.

-12. We do not believe that direct action is sufficient to achieve any of this. The habitual tactics

-of marching, holding signs, and establishing temporary autonomous zones risk becoming

-comforting substitutes for effective success. “At least we have done something” is the rallying

-cry of those who privilege self-esteem rather than effective action. The only criterion of a good

-tactic is whether it enables significant success or not. We must be done with fetishising

-particular modes of action. Politics must be treated as a set of dynamic systems, riven with

-conflict, adaptations and counter-adaptations, and strategic arms races. This means that each

-individual type of political action becomes blunted and ineffective over time as the other sides

-adapt. No given mode of political action is historically inviolable. Indeed, over time, there is an

-increasing need to discard familiar tactics as the forces and entities they are marshalled

-against learn to defend and counter-attack them effectively. It is in part the contemporary left’s

-inability to do so which lies close to the heart of the contemporary malaise.

-13. The overwhelming privileging of democracy-as-process needs to be left behind. The

-fetishisation of openness, horizontality, and inclusion of much of today’s ‘radical’ left set the

-

-stage for ineffectiveness. Secrecy, verticality, and exclusion all have their place as well in

-effective political action (though not, of course, an exclusive one).

-14. Democracy cannot be defined simply by its means – not via voting, discussion, or general

-assemblies. Real democracy must be defined by its goal – collective self-mastery. This is a

-project which must align politics with the legacy of the Enlightenment, to the extent that it is

-only through harnessing our ability to understand ourselves and our world better (our social,

-technical, economic, psychological world) that we can come to rule ourselves. We need to

-posit a collectively controlled legitimate vertical authority in addition to distributed horizontal

-forms of sociality, to avoid becoming the slaves of either a tyrannical totalitarian centralism or

-a capricious emergent order beyond our control. The command of The Plan must be married

-to the improvised order of The Network.

-15. We do not present any particular organisation as the ideal means to embody these

-vectors. What is needed – what has always been needed – is an ecology of organisations, a

-pluralism of forces, resonating and feeding back on their comparative strengths. Sectarianism

-is the death knell of the left as much as centralization is, and in this regard we continue to

-welcome experimentation with different tactics (even those we disagree with).

-16. We have three medium term concrete goals. First, we need to build an intellectual

-infrastructure. Mimicking the Mont Pelerin Society of the neoliberal revolution, this is to be

-tasked with creating a new ideology, economic and social models, and a vision of the good to

-replace and surpass the emaciated ideals that rule our world today. This is an infrastructure in

-the sense of requiring the construction not just of ideas, but institutions and material paths to

-inculcate, embody and spread them.

-17. We need to construct wide-scale media reform. In spite of the seeming democratisation

-offered by the internet and social media, traditional media outlets remain crucial in the

-selection and framing of narratives, along with possessing the funds to prosecute

-investigative journalism. Bringing these bodies as close as possible to popular control is

-crucial to undoing the current presentation of the state of things.

-18. Finally, we need to reconstitute various forms of class power. Such a reconstitution must

-move beyond the notion that an organically generated global proletariat already exists.

-Instead it must seek to knit together a disparate array of partial proletarian identities, often

-embodied in post-Fordist forms of precarious labour.

-19. Groups and individuals are already at work on each of these, but each is on their own

-insufficient. What is required is all three feeding back into one another, with each modifying

-the contemporary conjunction in such a way that the others become more and more effective.

-A positive feedback loop of infrastructural, ideological, social and economic transformation,

-generating a new complex hegemony, a new post-capitalist technosocial platform. History

-demonstrates it has always been a broad assemblage of tactics and organisations which has

-brought about systematic change; these lessons must be learned.

-20. To achieve each of these goals, on the most practical level we hold that the accelerationist

-left must think more seriously about the flows of resources and money required to build an

-effective new political infrastructure. Beyond the ‘people power’ of bodies in the street, we

-require funding, whether from governments, institutions, think tanks, unions, or individual

-benefactors. We consider the location and conduction of such funding flows essential to begin

-reconstructing an ecology of effective accelerationist left organizations.

-21. We declare that only a Promethean politics of maximal mastery over society and its

-environment is capable of either dealing with global problems or achieving victory over

-capital. This mastery must be distinguished from that beloved of thinkers of the original

-Enlightenment. The clockwork universe of Laplace, so easily mastered given sufficient

-information, is long gone from the agenda of serious scientific understanding. But this is not to

-align ourselves with the tired residue of postmodernity, decrying mastery as proto-fascistic or

-authority as innately illegitimate. Instead we propose that the problems besetting our planet

-and our species oblige us to refurbish mastery in a newly complex guise; whilst we cannot

-

-predict the precise result of our actions, we can determine probabilistically likely ranges of

-outcomes. What must be coupled to such complex systems analysis is a new form of action:

-improvisatory and capable of executing a design through a practice which works with the

-contingencies it discovers only in the course of its acting, in a politics of geosocial artistry and

-cunning rationality. A form of abductive experimentation that seeks the best means to act in a

-complex world.

-22. We need to revive the argument that was traditionally made for post-capitalism: not only is

-capitalism an unjust and perverted system, but it is also a system that holds back progress.

-Our technological development is being suppressed by capitalism, as much as it has been

-unleashed. Accelerationism is the basic belief that these capacities can and should be let

-loose by moving beyond the limitations imposed by capitalist society. The movement towards

-a surpassing of our current constraints must include more than simply a struggle for a more

-rational global society. We believe it must also include recovering the dreams which transfixed

-many from the middle of the Nineteenth Century until the dawn of the neoliberal era, of the

-quest of Homo Sapiens towards expansion beyond the limitations of the earth and our

-immediate bodily forms. These visions are today viewed as relics of a more innocent moment.

-Yet they both diagnose the staggering lack of imagination in our own time, and offer the

-promise of a future that is affectively invigorating, as well as intellectually energising. After all,

-it is only a post-capitalist society, made possible by an accelerationist politics, which will ever

-be capable of delivering on the promissory note of the mid-Twentieth Century’s space

-programmes, to shift beyond a world of minimal technical upgrades towards all-encompassing

-change. Towards a time of collective self-mastery, and the properly alien future that entails

-and enables. Towards a completion of the Enlightenment project of self-criticism and selfmastery, rather than its elimination.

-23. The choice facing us is severe: either a globalised post-capitalism or a slow fragmentation

-towards primitivism, perpetual crisis, and planetary ecological collapse.

-24. The future needs to be constructed. It has been demolished by neoliberal capitalism and

-reduced to a cut-price promise of greater inequality, conflict, and chaos. This collapse in the

-idea of the future is symptomatic of the regressive historical status of our age, rather than, as

-cynics across the political spectrum would have us believe, a sign of sceptical maturity. What

-accelerationism pushes towards is a future that is more modern – an alternative modernity

-that neoliberalism is inherently unable to generate. The future must be cracked open once

-again, unfastening our horizons towards the universal possibilities of the Outside.

-

diff --git a/_queue/celerity.markdown b/_queue/celerity.markdown

deleted file mode 100644

index 3974b9767b63d097cc50e15e9431b7dbd4dd8e37..0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

--- a/_queue/celerity.markdown

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,497 +0,0 @@

-#Celerity: A Critique of the Manifesto for an

-Accelerationist Politics

-McKenzie Wark

-0.0 You have to love any manifesto which gets to

-climate change in only its second paragraph. It shows

-a keen attention to the actual agenda of the times.

-This is not the least merit of #Accelerate: Manifesto for

-an Accelerationist Politics. It has at least some grasp of

-contemporary conjuncture in which we find

-ourselves. But the grasp is in my view, only partial. In

-some ways it’s a rather old-fashioned text. Of course,

-one is always drawing on the past to imagine a

-future. But this process – some would call it

-détournement, some would call it hacking – has to be

-done with a little more historical depth and breadth.

-What follows, then, is a friendly commentary and

-critique of #Accelerate. The numbering of these

-counter-theses match those of the original document.

-1.1 The widening gyre of the commodity economy is a

-series of what, after Marx, we can call metabolic rifts.

-In the division between exchange value and use

-value, commodity exchange severs objects from the

-matrices of their engendering. Only one side of the

-double form of value is subject to a quantitative

-feedback loop – exchange value. Its vestigial double –

-use value – or the mesh from which things are

-

-extracted, is not so easily quantified. And so rifts open

-up in the metabolic process. Rifts which political

-systems borne of the successive eras of commodity

-economy cannot even recognize as problems, let alone

-solve.

-1.2 Climate change is the most troubling of these rifts,

-but there are many others. The problem with the

-dynamic of the commodity economy is that the

-struggle within it of subordinated classes tends,

-among other things, to force the ruling class toward

-substituting technology for direct labor. But each of

-these substitutions draws in turn on more energy and

-more material resources. The whole infrastructure of

-the global commodity economy has by now

-committed itself to the consumption of more

-resources than may even exist. The ruling class, when

-not deluding itself with various ideological ruses,

-surely knows that maintaining a commodity economy

-on full speed ahead can only worsen various

-metabolic rifts, climate disruption among them. One

-suspects it is quietly preparing for this, arming itself,

-building its private arks.

-1.3 Against this hideous prospect, its high time for a

-new imaginary, a new space for thought and action.

-Such an imaginary already exists, but in fragments.

-The difficulty for subordinate classes is always the

-

-project of the totality, the very thing over which they

-have no power. Well, nobody has power over the

-totality as totality any more! The biosphere is in

-decline as a result of a mass of private interests

-competing to chop it into bits of exchange value. The

-challenge is to claim the totality, to open it, to put

-modernity back in play as a space affording more

-than one path to a viable future.

-1.4 The ruling class would like us to imagine that the

-‘neoliberal’ future is the only one. This term needs to

-be challenged on a number of fronts. Firstly, this is

-not a restoration of a liberal order. Its something new.

-It was not a turning back of the clock to a form of

-commodity economy prior to the welfare state and all

-the other compromises wrested from the ruling class

-by organized labor and the social movements. It’s a

-new stage, based on new technical infrastructures,

-new forms of control. Secondly: what makes anyone

-think capitalism was ever ‘liberal’ in the first place?

-The autonomy of the economic sphere is itself an

-ideological proposition. The ‘liberal’ economic sphere

-was achieved through massive state violence against

-premodern peoples and their ways of life. So: there

-was no liberal capitalism; there is no neoliberal

-capitalism. But there is a new stage of the commodity

-economy whose contours are rather undefined

-

-theoretically, and not least because the left buys into

-the ‘neoliberal’ myth as much as the right.

-1.5 In the overdeveloped world of Europe, the United

-States and Japan, class composition has changed

-significantly. Manufacturing has declined within the

-composition of labor. The pressure points that

-organized labor used to have at which to struggle for

-its interests are no longer within reach. Even if we

-could shut down all the hair salons it would not have

-the same effect as shutting down a strategic industry

-like steel. Now that such strategic industries are often

-not located in the overdeveloped world, the ruling

-class has less and less interest in maintaining the

-conditions of reproduction within the space of the old

-overdeveloped nations. If your big investments are

-not there, then why care about the health or education

-of those workers? The old Keynsian solutions to the

-current crisis would in fact work very well, but there

-is no coalition of interest for them, and significant

-ruling class pressure to use the crisis to reduce the

-reproductive functions of the state. In any case, the

-emerging forms of commodification take aim at

-precisely the affective labor and informational labor

-that the state usually still provides, in health and

-education. The overdeveloped world offers few new

-domains for commodification, so these old socialized

-ones become targets.

-

-1.6 The diffusion of commodity relations throughout

-the whole domain of the overdeveloped world

-fragments and renders more and more molecular the

-points of conflict and struggle. Local and specific

-forms of challenge arise, from Occupy Wall Street to

-the quiet, passive ‘Bartleby’ tactics of not doing

-anything at work you don’t really have to do. The

-problem is finding forms of semantic glue to stitch

-such actions together rhetorically. This need not be a

-radical language, it just needs to be a plausible one. A

-popular poetics of the open totality, of there being

-more than one possible future, and more than one

-possible path out of the present.

-2.0 Celerity

-2.0 Not so fast, you may say. Let’s not get caught up

-in too quick a dismissal of existing forms of theory

-and praxis. While the manifesto form thrives on the

-pure annihilation of the past, let’s proceed will all

-deliberate speed, but not too haphazardly.

-2.1 To begin with: while the commodity economy

-presents itself as forward-moving, even as

-‘progressive’, let’s challenge that myth. It seems that a

-large part of what the ruling class is now doing in the

-overdeveloped world is cultivating and defending

-

-quasi-monopoly conditions. Using the archaic patent

-system to shut out any whipper-snappers, or to joust

-with each other for turf. Meanwhile, what the ruling

-class seems to be doing in the so-called

-underdeveloped world is rolling out the old

-industrial paradigm of the nineteenth century on a

-massive scale. It encounters there in modified form

-the recalcitrance of labor, and responds with the same

-spectacular offerings, which are met with the same

-boredom, again, on an expanded scale. The relations

-of production of the commodity economy seem more

-a fetter on the free development of new social and

-technical arrangements, new kinds of future, than

-their custodians. The commodity form itself is out of

-date.

-2.2 There’s something to be said for the thought

-exercise of imagining where the commodity form, left

-to accelerate according to its own one-track mind,

-would end up. Its replacement of recalcitrant labor by

-capital would become absolute, making labor

-obsolete, like a vestigial organ. If only there were

-enough energy and resources left. It might even make

-not only labor but the ruling class obsolete. A whole

-planet ticking over via silicon encrusting bits! But this

-is only a thought exercise, a fatal strategy in theory. In

-practice there’s not enough planet left to entertain

-such an idea. Besides: technology may have agency

-

-but it isn’t absolute. It is pressed this way and that by

-competing class interests. Even when it seems like

-alternate paths to the future are foreclosed, there’s

-always struggle, internal differentiation. There’s

-always points that can be prized open.

-2.3 Opening the path to other futures means

-reopening the qualitative dimension of modernity, its

-aesthetic dimension. This was the chosen terrain of its

-avant-gardes: the futurists and constructivists, the

-surrealists and situationists, the accelerationists and

-schizomaniacs. All of which opened up futures that

-have now been foreclosed. But: to make three steps

-forward, two steps back. There are many resources in

-the aesthetic alter-modern spaces of the past via

-which to experiment with steps forward.

-2.4 All these qualitative avant-gardes met their

-Waterloo: the quantitative rear-guard. The path to

-sustaining the commodity economy after the

-challenges of organized labor and the social

-movements reached its peak was a new kind of

-quantification, a new logistics, a new mesh of vectors

-for command and control. Initially it was crude and

-dealt only with aggregates and proxies, like the early

-computer simulations of the cold war. But what really

-led to its dominance is the embedding in everyday

-life itself of the production of the quantitative data for

-

-its expansion to the whole of life. Thus, the qualitative

-avant-gardes have to re-imagine possible spaces for

-alter-modernities based on this transformation of

-everyday life in all its forms into a gamespace of

-quantified data. Just as the situationists imagined a

-space of play in the interstitial spaces of the policing

-of the city via the dérive, so too we now have to

-imagine and experiment with emerging gaps and

-cracks in the gamespace that the commodity economy

-has become. The time of the hack, or the exploit, is at

-hand.

-2.5 Here we can follow in the path of Marx, but not by

-treating him scholastically. Rather, one has to

-reinvent his practice: his use of conceptual tools as

-tools, his use of the best empirical data, his

-attunement to the struggles around him, his

-deployment of the communicative strategies of

-modernity itself. Moreover, we need to recover

-Marx’s version of the Nietzschian slogan: “god is

-dead.” For Marx, history is not transitive. There’s no

-going back. There’s only forward. It’s a question of

-struggling to open another future besides this one

-which, as he himself intuited, has no future at all. So:

-let’s look not at what Marx says, but what he does.

-Let’s align ourselves, as he did, with the avant garde

-of the times.

-

-2.6 There’s little to be gained from re-hashing the

-various experiments in twentieth century revolution.

-Lenin and Mao have little to teach us. Their situation

-is not our situation. The rest is moot.

-2.7 Who are the forces for social change? Marx asks

-this in his Manifesto. And his answer: those who ask

-the property question. It turns out that putting all

-property in the hands of the state is not the right

-answer to the property question. Goodbye Lenin;

-goodbye Mao. But the question remains a valid one.

-Who are the agents struggling in and against the

-emergent productive forms who can shape the

-affordances of those technologies and labor

-processes? One of the answers is: the worker. But

-another is: the ‘hacker’. The worker is the one who

-struggles in and against a productive regime. The

-hacker is the one who contributes to designing new

-ones, or at the very least populating the existing ones

-with new concepts, new ideas – recuperated by the

-new property forms of so-called ‘intellectual

-property’. These are the accelerators of modernity:

-those who labor in and against it. These are the ones

-for whom the regime of the commodity economy is as

-much fetter as enabler. The relation between these

-classes, and with other subaltern classes, becomes the

-key tactical issue. An issue of not just a poetics of an

-open future, but modes of coordination.

-

-3.0 Futurity

-3.1 The task is one of coordinating the latent energies

-of a people bored with what the commodity has to

-offer with the awareness of what shaping powers

-remain to us to open cracks towards new futures. It’s

-not either or. ‘Folk politics’ and technical politics need

-to talk to each other. To do otherwise is to lapse, on

-the one hand, into local and specific grievances, or

-purely negative energies, or a refusal to confront the

-larger picture of metabolic rift. On the other hand, to

-ignore folk politics is also a danger, the danger of the

-technocratic fix. It’s to base decisions on a refusal to

-acknowledge folk struggle and demand, but also

-insight and information from the popular struggles in

-and against commodity economy. What we need is

-neither abstraction nor occupying, but the occupying of

-abstraction.

-3.2 It’s a question of whether boredom with the

-commodity economy will work fast enough, as it

-spreads from the overdeveloped world to the

-underdeveloped, to open up a new path before

-metabolic rifts like the climate crisis forces the planet

-toward more violent, disorganizing, and frankly

-fascist ‘solutions’ to its problems. Already in China

-factory workers are starting to get restless. Beyond

-that, there’s only so much cheap labor left on the

-planet to exploit. Meanwhile, in the overdeveloped

-

-world, a rather novel regime of value extraction is

-finding ways to extract value from non-work. Search

-engines and social networking find ways to extract

-value from activity regardless of whether it is ‘work’

-and without paying for it. It’s a kind of vulture

-industry, parasitic on frankly successful popular

-struggles to free vast tracts of information from the

-commodity form and circulate it freely. But having

-beaten back the old culture industries with this tactic,

-the social movement that was free culture finds itself

-recuperated at a higher level of abstraction by the

-vulture industries and their ‘gamification’ of every

-aspect of everyday life. So: any alter-modernity

-project has to bypass the expansion of the old

-commodification regimes across the planet, but also

-these curious new ones, dominant in the

-overdeveloped world, but tending now to transform

-information flows everywhere.

-3.3 Of course, part of the old ruling class still insists

-on increasingly repressive and global measures to

-restrict information to the old property form, whether

-of patent or copyright or trademark. But the current

-productive regime respects no such antiquated

-embedding of information into particular objects.

-“Information wants to be free but is everywhere in

-chains.” But it has in part been sidestepped by

-another faction of the ruling class itself, which finds

-

-ways to extract value from the spontaneous, popular

-gift economies of information that have sprung up.

-New tactics are called for now, to work against the

-new forms of commodification as well as the old.

-Perhaps it would even be possible to design more

-efficient and useful technical and social relations, no

-matter how lo-tech, precisely because they would not

-require the cumbersome ‘digital rights management’

-and so forth of the old fettered regime.

-3.4 While there may be no going back to the old

-Fordist models of production, the partial

-socializations of the surplus that were the fruit of

-struggle of that time have much to recommend them.

-It really is the case that these ‘socialist’ systems of

-housing, healthcare and education outperformed

-their profiteering cousins. The ideology of the times

-denies this, but it’s the case. These efficient systems

-are being carved up in the overdeveloped world for

-no better reason than to produce inefficient copies of

-them which enable the ruling class to extract a

-surplus from something. Let’s never forget: it may not

-have been utopia, but socialism succeeded, in the west,

-in these domains.

-3.5 Building better futures will take all the technical

-infrastructure we can get. But it’s not as simple as

-repurposing existing infrastructures, all of which are

-

-based on ever-expanding resource use and labor

-exploitation as design givens. The first step forward is

-to get out of either/or language about technology. So

-much discussion either sees it as panacea or curse.

-Technology, as Stiegler says, is a pharamakon: its both,

-and everything in between. A technology is not what

-it does, it is also what it might do. We need an openended, experimental approach, a critical design

-approach. Being ‘for’ or ‘against’ it is one of the old

-problems of an unhelpful discourse of modernity.

-3.6 One of the best of the ‘socialist’ systems of the

-west was publicly funded big science. Science was

-always subordinated to national security and

-industrial development goals, but it was not identical

-to them. The internet was invented more or less by

-accident. Most of the breakthroughs happened before

-science was narrowly constrained to producing value

-for the commodity economy or specific defense needs.

-We need to recover a sense of the possibility of

-science. Most of its failures were not failures of

-science, but failures of politics. Pesticides like DDT

-cause damage because of a failure of the feedback

-loop from folk politics to technocratic decision

-making. The same is true of so many toxic disasters

-today. Indeed, one needs science to know when the

-product of a science is being misapplied. Climate

-science is the reason we know so much of applied

-

-science in industry is causing problems. We need

-more science, not less. Including a science of popular

-knowledge of the effects of applied industrial science.

-3.7 Even a little techno-utopianism might not be a bad

-thing from time to time, to imagine possible spaces,

-even if only conceptual spaces, like in the work of

-Constant. But if we acknowledge that tech on its own

-can’t save us, then we need to be attendant also to

-experiments in ‘social’ technology. Horizontalism, for

-example, as practiced in Occupy Wall Street and

-elsewhere, is also a technology. Whether it’s a technoutopia one is embarked upon, or a new social

-practice, one has to pay attention to how the social

-inhabits the former and the technical permeates the

-latter. Tech and the social (or the political) are not

-separate things. The phrase “the technological is

-politically (or socially) constructed” is meaningless.

-One is simply looking at the same systems through

-different lenses when one speaks of the political or

-the technical. But among intellectuals, the social, the

-political (and we can add the cultural) are something

-of a fetish. There’s something tactically useful in

-stressing the technical bases of all such perspectives.

-Among engineers and designers, of course, the

-opposite thinking strategy applies. Accelerating

-technical evolution requires a conversation that is

-

-sophisticated in such matters, and which includes all

-perspectives, including ‘folk’ ones.

-3.8 There can be no return to ‘planning’ as a panacea,

-however, as it always implies asymmetries of

-information. The excluded parties and their

-knowledge, their struggles, always turn out to be

-relevant. We need only look at the ecological disasters

-of Soviet planning for examples. The challenge is to

-coordinate qualitative knowledge as well as the

-market coordinates quantitative knowledge – and

-better.

-3.9 New kinds of quantitative measure can also help.

-Let’s use that weapon against the ruling class! But we

-also need new visualization tools, new narratives,

-new poetics. And ones which do not exclude ‘folk

-politics’ but rather include them. The question to ask

-about any new ‘cognitive mediator’ is: whose cognition

-is it mediating?

-3.10 The emphasis for an alter-modernity at this point

-has to be on its experimental practices. This means a

-synthesis not just of the qualitative and quantitative

-dimensions of modernity but also threading back

-together its critical, negative tendencies and its

-affirmative, design-based ones.

-

-3.11 All this calls for a gathering of social forces. It

-requires cross-class alliances, of workers and hackers.

-It requires transnational networks, spanning the

-overdeveloped and underdeveloped worlds. It’s not

-simply a matter of ‘reprogramming’ existing technical

-infrastructures. It’s a question of aligning the

-tendencies which struggle within it at all its points.

-3.12 It is no longer enough to say what an ideal

-‘politics’ might be. Perhaps ‘politics’ itself needs to

-become an object of sever critique. Intellectuals like to

-imagine an ideal version of politics, but are less keen

-on the actually existing ones. It’s a question of finding

-the right job for those of us who talk and write and

-don’t do much else. Perhaps as agents of a low theory,

-which tries to link up particular struggles, rather than

-plan it, top down. Let’s talk no more of what politics

-‘ought’ to be like. Comrades, roll up your sleeves!

-3.13 Certainly let’s not retreat too far back towards

-the secrecy, verticality and exclusion which got us

-into this mess in the first place. Planning has its place.

-Every economy plans. But too much closure just leads

-to information deficits.

-3.14 Neither the command of the plan nor the purely

-horizontal participatory model works on its own.

-They exist in tension with each other, and with many

-

-other social forms. Let’s play with a full deck of social

-forms.

-3.15 There is always an ecology of organizations, of a

-sort. But the problem with the current one is that it

-does not reproduce its own conditions of existence. It

-destroys them. This must be a central object of both

-critique and experiment at all levels.

-3.16 Retreating to the mountain, equipping some

-ruling elite with a new ideology and a few cognitive

-tools – only prolongs the crisis. Let’s not dally with

-the fantasy of a new prince of Syracuse.

-3.21 The Promethean mythology of the futurists

-might work for some, but a more capacious and

-global deployment of the mythic stock of images and

-stories is more what the times call for. Besides, what

-happened to Prometheus?

-3.24 The prospect of a future does however need

-reconstruction. It might begin with a synthesis of

-various strands of modernity that are now

-fragmented into separate realms, all under the reign

-of the commodity and its quantitative equivalence.

-But such a prospect means nothing without

-identifiable social actors. It calls for a popular, and

-populist, struggle, in many languages, drawing

-

-different modes of thought and experiment into

-common projects. It may not need an over-arching

-image or metaphor. Fordist models even in ideology

-seem a thing of the past. The task is not political

-rhetoric but an actually political one, of finding the

-modus vivendi for different forces in struggle, acting

-now with the utmost celerity.

-4.0 Personal Concluding Thoughts

-4.0 So: Two cheers for #Accelerate. But only two. It

-successfully develops the provocative writing of Nick

-Land, and to his left. But if Land is a ‘rightaccelerationist’, #Acclerate ends up being something

-of a centrist-accelerationist position. It defaults to

-planning, to the intellectual retreat up to the

-mountain, rather than engaging with new forms of

-struggle. Still, its reanimated futurism, its openness

-toward technology, to thinking problems at scale,

-these are positive features. What remains is to push it

-a little toward a more ‘left-accelerationist’ position,

-without lapsing into the sins of the left: the fetish of

-politics as the magical solution to everything high

-among them.

-4.1 To the extent that personally I find common

-ground here is that #Accelerate overlaps with a

-position I started to stake out ten years ago now, in A

-

-Hacker Manifesto (Harvard UP 2004) and Gamer

-Theory (Harvard UP 2007). Those texts reflect the

-positive and more pessimistic dimensions of

-accelerationism respectively. I drew on different

-modernist avant garde resources, the genealogy of

-which I then sketched out in The Beach Beneath the

-Street (Verso, 2011) and The Spectacle of Disintegration

-(Verso 2013). In short: there’s other paths to the same

-territory besides the strange one that wends from Karl

-Marx via Georges Bataille to Nick Land. (Deleuze,

-however, we have in common). Perhaps the collective

-project is remap that territory, so we know better

-what our options are in what resources can be drawn

-from the past. Otherwise: damn the torpedoes, full

-speed ahead.

-

diff --git a/_queue/jopp_hacklabs-and-hackerspaces.md b/_queue/jopp_hacklabs-and-hackerspaces.md

deleted file mode 100644

index a6804fb78313d4be76007002970243a1ddc8f78f..0000000000000000000000000000000000000000

--- a/_queue/jopp_hacklabs-and-hackerspaces.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,1146 +0,0 @@

-http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/peer-reviewed-papers/hacklabs-and-hackerspaces/

-

-· Hacklabs and hackerspaces – tracing two genealogies

-

-**Maxigas**

-

-1. Introduction

----------------

-

-It seems very promising to chart the genealogy of hackerspaces from the

-point of view of hacklabs, since the relationship between these scenes

-have seldom been discussed and largely remains unreflected. A

-methodological examination will highlight many interesting differences

-and connections that can be useful for practitioners who seek to foster

-and spread the hackerspace culture, as well as for academics who seek to

-conceptualise and understand it. In particular, hackerspaces proved to

-be a viral phenomenon which may have reached the height of its

-popularity, and while a new wave of fablabs spring up, people like

-Grenzfurthner and Schneider (2009) have started asking questions about

-the direction of these movements. I would like to contribute to this

-debate about the political direction and the political potentials of

-hacklabs and hackerspaces with a comparative, critical,

-historiographical paper. I am mostly interested in how these intertwined

-networks of institutions and communities can escape the the capitalist

-apparatus of capture, and how these potentialities are conditioned by a

-historical embeddedness in various scenes and histories.

-

-Hacklabs manifest some of the same traits as hackerspaces, and, indeed,

-many communities who are registered on hackerspaces.org identify

-themselves as “hacklabs” as well. Furthermore, some registered groups

-would not be considered to be a “real” hackerspace by most of the

-others. In fact, there is a rich spectrum of terms and places with a

-family resemblance such as “coworking spaces”, “innovation

-laboratories”, “media labs”, “fab labs”, “makerspaces”, and so on. Not

-all of these are even based on an existing community, but have been

-founded by actors of the formal educational system or commercial sector.

-It is impossible to clarify everything in the scope of a short article.

-I will therefore only consider community-led hacklabs and hackerspaces

-here.

-

-Despite the fact that these spaces share the same cultural heritage,

-some of their ideological and historical roots are indeed different.

-This results in a slightly different adoption of technologies and a

-subtle divergence in their organisational models. Historically speaking,

-hacklabs started in the middle of the 1990s and became widespread in the

-first half of the 2000s. Hackerspaces started in the late 1990s and

-became widespread in the second half of the 2000s. Ideologically

-speaking, most hacklabs have been explicitly politicised as part of the

-broader anarchist/autonomist scene, while hackerspaces, developing in

-the libertarian sphere of influence around the Chaos Computer Club, are

-not necessarily defining themselves as overtly political. While

-practitioners in both scenes would consider their own activities as

-oriented towards the liberation of technological knowledge and related

-practices, the interpretations of what is meant by “liberty” diverges.

-One concrete example of how these historical and ideological divergences

-show up is to be found in the legal status of the spaces: while hacklabs

-are often located in squatted buildings, hackerspaces are generally

-rented.

-

-This paper is comprised of three distinct sections. The first two

-sections draw up the historical and ideological genealogy of hacklabs

-and hackerspaces. The third section brings together these findings in

-order to reflect on the differences from a contemporary point of view.

-While the genealogical sections are descriptive, the evaluation in the

-last section is normative, asking how the differences identified in the

-paper play out strategically from the point of view of creating

-postcapitalist spaces, subjects and technologies.

-

-Note that at the moment the terms “hacklab” and “hackerspace” are used

-largely synonymously. Contrary to prevailing categorisation, I use

-hacklabs in their older (1990s) historical sense, in order to highlight

-historical and ideological differences that result in a somewhat

-different approach to technology. This is not linguistic nitpicking but

-meant to allow a more nuanced understanding of the environments and

-practices under consideration. The evolving meaning of these terms,

-reflecting the social changes that have taken place, is recorded on

-Wikipedia. The Hacklab article was created in 2006 (Wikipedia

-contributors, 2010a), the Hackerspace article in 2008 (Wikipedia

-contributors, 2011). In 2010, the content of the Hacklab article was

-merged into the Hackerspaces article. This merger was based on the

-rationale given on the corresponding discussion page (Wikipedia

-contributors, 2010). A user by the name “Anarkitekt” wrote that “I’ve

-never heard or read anything implying that there is an ideological

-difference between the terms hackerspace and hacklab” (Wikipedia

-contributors, 2010b). Thus the treatment of the topic by Wikipedians

-supports my claim that the proliferation of hackerspaces went hand in

-hand with a forgetting of the history that I am setting out to

-recapitulate here.

-

-

-

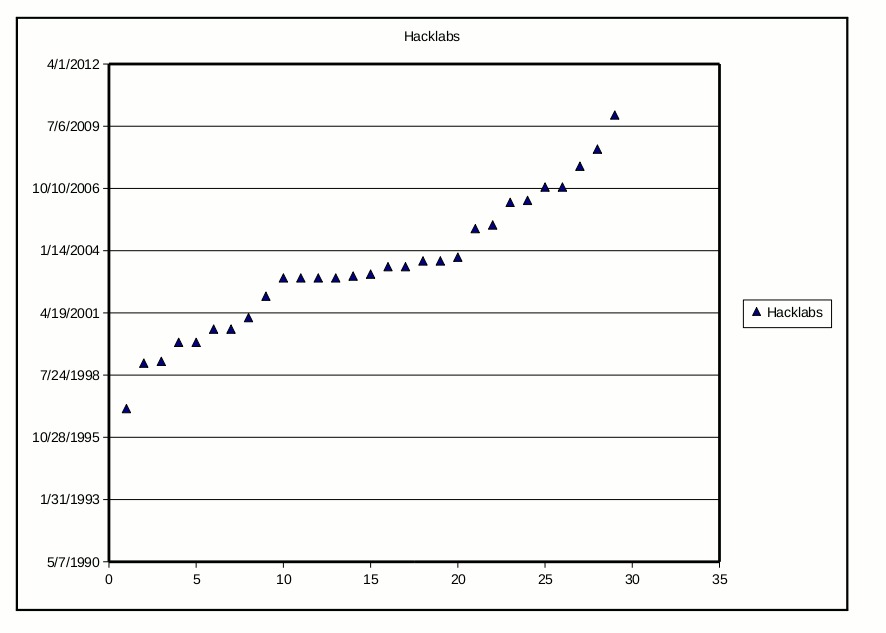

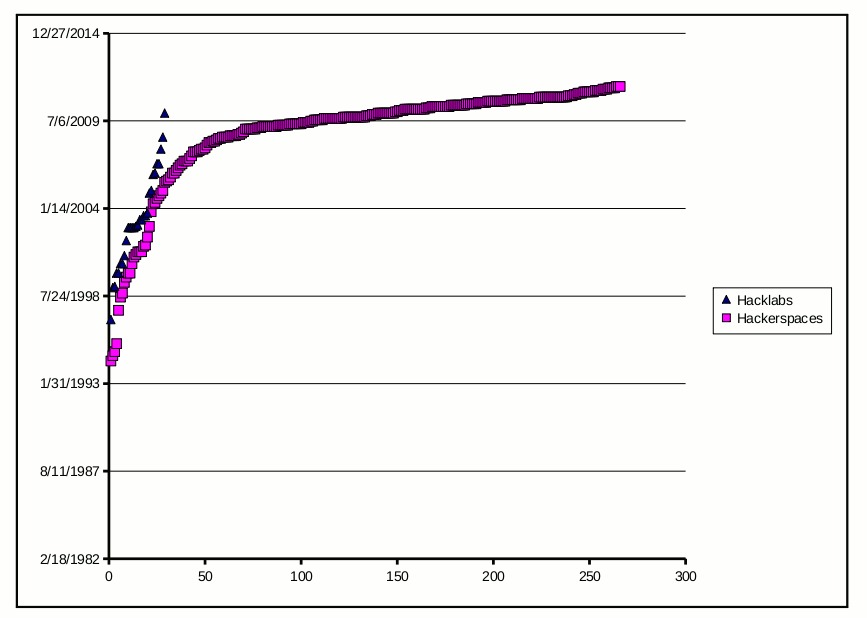

-Figure 1. Survey of domain registrations of the hacklabs list from

-hacklabs.org

-

-2. Hacklabs

------------

-

-The surge of hacklabs can be attributed to a number of factors. In order

-to sketch out their genealogy, two contexts will be expanded on here:

-the autonomous movement and media activism. A shortened and simplified

-account of these two histories are given that emphasises elements that

-are important from the point of view of the emergence of hacklabs. The

-hacker culture, of no less importance, will be treated in the next

-section in more detail. A definition from a seminal article by Simon

-Yuill highlights the basic rationales behind these initiatives (2008):

-

-“Hacklabs are, mostly, voluntary-run spaces providing free public access

-to computers and internet. They generally make use of reclaimed and

-recycled machines running GNU/Linux, and alongside providing computer

-access, most hacklabs run workshops in a range of topics from basic

-computer use and installing GNU/Linux software, to programming,

-electronics, and independent (or pirate) radio broadcast. The first

-hacklabs developed in Europe, often coming out of the traditions of

-squatted social centres and community media labs. In Italy they have

-been connected with the autonomist social centres, and in Spain,

-Germany, and the Netherlands with anarchist squatting movements.”

-

-The autonomous movement grew out of the “cultural shock” (Wallerstein,

-2004) of 1968 which included a new wave of contestations against

-capitalism, both in its welfare state form and in its Eastern

-manifestation as “bureaucratic capitalism” (Debord [1970], 1977). It was

-concurrently linked to the rise of youth subcultures. It was mainly

-oriented towards mass direct action and the establishment of initiatives

-that sought to provide an alternative to the institutions operated by

-state and capital. Its crucial formal characteristic was

-self-organisation emphasising the horizontal distribution of power. In

-the 1970s, the autonomous movement played a role in the politics of

-Italy, Germany and France (in order of importance) and to a lesser

-extent in other European countries like Greece (Wright, 2002). The

-theoretical basis is that the working class (and later the oppressed in

-general) can be an independent historical actor in the face of state and

-capital, building its own power structures through self-valorisation and

-appropriation. It drew from orthodox Marxism, left-communism and

-anarchism, both in theoretical terms and in terms of a historical

-continuity and direct contact between these other movements. The rise

-and fall of left wing terrorist organisations, which emerged from a

-similar milieu (like the RAF in Germany or the Red Brigade in Italy),

-has marked a break in the history of the autonomous movements.

-Afterwards they became less coherent and more heterogenous. Two specific

-practices that were established by autonomists are squatting and media

-activism (Lotringer Marazzi, 2007).

-

-The reappropriation of physical places and real estate has a much longer

-history than the autonomous movement. Sometimes, as in the case of the

-pirate settlements described by Hakim Bey (1995,, 2003), these places

-have evolved into sites for alternative “forms of life” (Agamben, 1998).

-The housing shortage after the Second World War resulted in a wave of

-occupations in the United Kingdom (Hinton, 1988) which necessarily took

-on a political character and produced community experiences. However,

-the specificity of squatting lay in the strategy of taking occupied

-houses as a point of departure for the reinvention of all spheres of

-life while confronting authorities and the “establishment” more

-generally conceived. While many houses served as private homes,

-concentrating on experimenting with alternative life styles or simply

-satisfying basic needs, others opted to play a public role in urban

-life. The latter are called “social centres”. A social centre would

-provide space for initiatives that sought to establish an alternative to

-official institutions. For example, the infoshop would be an alternative

-information desk, library and archive, while the bicycle kitchen would

-be an alternative to bike shops and bike repair shops. These two

-examples show that among the various institutions to be replaced, both

-those operated by state and capital were included. On the other hand,

-both temporary and more or less permanently occupied spaces served as

-bases, and sometimes as front lines, of an array of protest activities.

-

-With the onset of neoliberalism (Harvey, 2005; 2007), squatters had to

-fight hard for their territory, resulting in the “squat wars” of the

-90s. The stake of these clashes that often saw whole streets under

-blockade was to force the state and capital to recognise squatting as a

-more or less legitimate social practice. While trespassing and breaking

-in to private property remained illegal, occupiers received at least

-temporary legal protection and disputes had to be resolved in court,

-often taking a long time to conclude. Squatting proliferated in the

-resulting ”grey area”. Enforcement practices, squatting laws and

-frameworks were established in the UK, Catalonia, Netherlands and

-Germany. Some of the more powerful occupied social centres (like the EKH

-in Vienna) and a handful of strong scenes in certain cities (like

-Barcelona) managed to secure their existence into the first decade of

-the 21^st^twenty first century. Recent years saw a series of crackdowns

-on the last remaining popular squatting locations such as the

-abolishment of laws protecting squatters in the Netherlands (Usher,,

-2010) and discussion of the same in the UK (House of Commons,, 2010).

-

-Media activism developed along similar lines, building on a long

-tradition of independent publishing. Adrian Jones (2009) argues for a

-structural but also historical continuity in the pirate radio practices

-of the 1960s and contemporary copyright conflicts epitomised by the

-Pirate Bay. On the strictly activist front, one important early

-contribution was Radio Alice (est., 1976) which emerged from the the

-autonomist scene of Bologna (Berardi Mecchia, 2007). Pirate radio and

-its reformist counterparts, community radio stations, flourished ever

-since. Reclaiming the radio frequency was only the first step, however.

-As Dee Dee Halleck explains, media activists soon made use of the

-consumer electronic products such as camcorders that became available on

-the market from the late 80s onwards. They organised production in

-collectives such as Paper Tiger Television and distribution in

-grassroots initiatives such as Deep Dish TV which focused on satellite

-air time (Halleck, 1998). The next logical step was information and

-communication technologies such as the personal computer — appearing on

-the market at the same time. It was different from the camcorder in the

-sense that it was a general purpose information processing tool. With

-the combination of commercially available Internet access, it changed

-the landscape of political advocacy and organising practices. At the

-forefront of developing theory and practice around the new communication

-technologies was the Critical Art Ensemble. It started with video works

-in 1986, but then moved on to the use of other emerging technologies

-(Critical Art Ensemble, 2000). Although they have published exclusively

-Internet-based works like *Diseases of the Consciousness* (1997), their

-*tactical media* approach emphasises the use of the right tool for the

-right job. In 2002 they organised a workshop in New York’s Eyebeam,

-which belongs to the wider hackerspace scene. New media activists played

-an integral part in the emergence of the alterglobalisation movement,

-establishing the Indymedia network. Indymedia is comprised of local

-Independent Media Centres and a global infrastructure holding it

-together (Morris 2004 gives a fair description). Focusing on open

-publishing as an editorial principle, the initiative quickly united and

-involved so many activists that it became one of the most recognised

-brands of the alterglobalisation movement, only slowly falling into

-irrelevance around the end of the decade. More or less in parallel with

-this development, the telestreet movement was spearheaded by Franco

-Berardi, also known as Bifo, who was also involved in Radio Alice,

-mentioned above. OrfeoTv was started in 2002 and used modified

-consumer-grade television receivers for pirate television broadcast (see

-Telestreet, the Italian Media Jacking Movement, 2005). Although the

-telestreet initiative happened on a much smaller scale than the other

-developments outlined above, it is noteworthy because telestreet

-operators reverse-engineered mass products in the same manner as

-hardware hackers do.

-

-Taking a cue from Situationism with its principal idea of making

-interventions in the communication flow as its point of departure, the

-media activists sought to expand what they called “culture jamming” into

-a popular practice by emphasising a folkloristic element (Critical Art

-Ensemble, 2001). Similarly to the proletarian educational initiatives of

-the classical workers’ movements (for example Burgmann 2005:8 on

-Proletarian Schools), such an approach brought to the fore issues of

-access, frequency regulations, popular education, editorial policies and

-mass creativity, all of which pointed in the direction of lowering the

-barriers of participation for cultural and technological production in

-tandem with establishing a distributed communication infrastructure for

-anticapitalist organising. Many media activists adhered to some version

-of Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony, taking the stand that cultural

-and educational work is as important as directly challenging property

-relations. Indeed, this work was seen as in continuation with

-overturning those property relations in the area of media, culture and

-technology. This tendency to stress the importance of information for

-the mechanism of social change was further strengthened by claims

-popularised by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri that immaterial and

-linguistic labour are the hegemonic mode of production in the

-contemporary configuration of capitalism (2002, 2004). At the extreme

-end of this spectrum, some argued that decisive elements of politics

-depend on a performance of representation, often technologically

-mediated, placing media activism at the centre of the struggle against

-state and capitalism. Irrespectivly of these ideological beliefs,

-however, what distinguished the media practitioners in terms of identity

-is that they did not see themselves simply as outsiders or service

-providers, but as an integral part of a social movement. As Söderberg

-demonstrates (2011), political convictions of a user community can be an

-often overlooked enabler of technological creativity.

-

-These two intertwined tendencies came together in the creation of

-hacklabs. Squats, on the one hand, closely embedded in the urban flows

-of life, had to use communication infrastructures such as Internet

-access and public access to terminals. Media activists, on the other

-hand, who are more often than not also grounded in a a local community,

-needed venues to convene, produce, teach and learn. As Marion Hamm

-observes when discussing how physical and virtual spaces enmeshed due to

-the activists’ use of electronic media communication: “This practice is

-not a virtual reality as it was imagined in the eighties as a graphical

-simulation of reality. It takes place at the keyboard just as much as in

-the technicians’ workshops, on the streets and in the temporary media

-centres, in tents, in socio-cultural centres and squatted houses.”

-(Translated by Aileen Derieg,, 2003). One example of how these lines

-converge is the Ultralab in Forte Prenestino, an occupied fortress in

-Rome which is also renowned for its autonomous politics in Italy. The

-Ultralab is declared to be an “emergent pattern” on its website

-(AvANa.net, 2005), bringing together various technological needs of the

-communities supported by the Forte. The users of the social centre have

-a shared need for a local area computer network that connects the

-various spaces in the squat, for hosting server computers with the

-websites and mailing lists of the local groups, for installing and

-maintaining public access terminals, for having office space for the

-graphics and press teams, and finally for having a gathering space for

-the sharing of knowledge. The point of departure for this development

-was the server room of AvANa, which started as a bulletin board system

-(BBS), that is, a dial-in message board in 1994 (Bazichelli 2008:80-81).

-As video activist Agnese Trocchi remembers,

-

-“AvANa BBS was spreading the concept of Subversive Thelematic: right to

-anonymity, access for all and digital democracy. AvANa BBs was

-physically located in Forte Prenestino the older and bigger squatted

-space in Rome. So at the end of the 1990’s I found myself working with

-technology and the imaginative space that it was opening in the young

-and angry minds of communities of squatters, activist and ravers.”

-(quoted in Willemsen, 2006)

-

-AvANa and Forte Prenestino connected to the European Counter Network

-(now at ecn.org), which linked several occupied social centres in Italy,

-providing secure communication channels and resilient electronic public

-presence to antifascist groups, the Disobbedienti movement, and other

-groups affiliated with the autonomous and squatting scenes. Locating the

-nodes inside squats had their own drawbacks, but also provided a certain

-level of physical and political protection from the authorities.

-

-Another, more recent example is the short lived Hackney Crack House, a

-hacklab located on 195 Mare Street in London. This squat situated in an

-early Georgian house was comprised of a theatre building, a bar, two

-stores of living spaces and a basement that housed a bicycle workshop

-and a studio space (see Foti, 2010). The hacklab provided a local area

-network and a media server for the house, and served as a tinkering

-space for the technologically inclined. During events like the Free

-School, participants, including both absolute beginners and more

-dedicated hobbyists, could learn to use free and open source

-technologies, network security and penetration testing. Everyday

-activities ranged from fixing broken electronics through building

-large-scale mixed media installations to playing computer games.

-

-The descriptions given above serve to indicate how hacklabs grew out of

-the needs and aspirations of squatters and media activists. This history

-comes with a number of consequences. Firstly, that the hacklabs fitted

-organically into the anti-institutional ethos cultivated by people in

-the autonomous spaces. Secondly, they were embedded in the political

-regime of these spaces, and were subject to the same forms of frail

-political sovereignty that such projects develop. Both Forte Prenestino

-and Mare Street had written and unwritten conducts of behaviour which

-users were expected to follow. The latter squat had an actively

-advertised Safer Places Policy, stating for instance that people who

-exhibit sexist, racist, or authoritive behaviour should expect to be

-challenged and, if necessary, excluded. Thirdly, the politicised logic